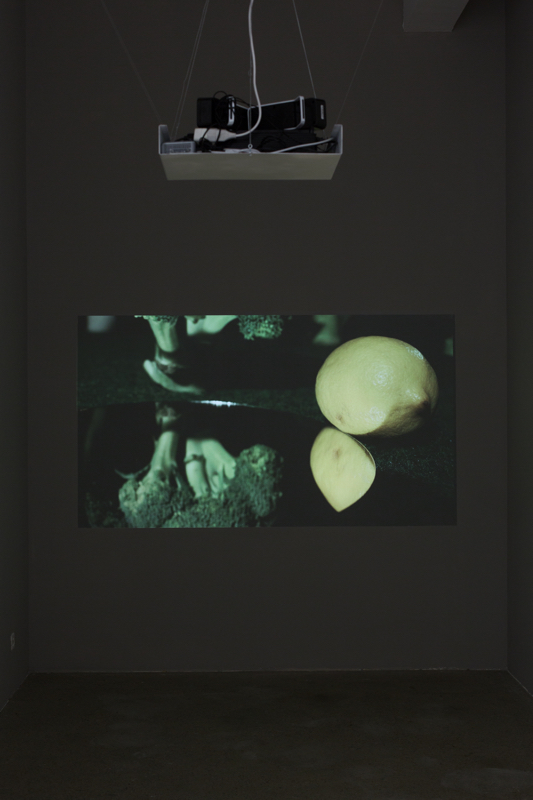

Klodin Erb, 3 February 2017 – 18 March 2017

"The Sweet Lemon Ballad", 2016

Video still, 13 min 13 sec

THE SWEET LEMON BALLAD

OPENING THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 2, 6 PM onwards

The Phenomenology of a Lemon

An essay by Stefan Zweifel on the film The Sweet Lemon Ballad by Klodin Erb

There it lies, beautifully at one with itself in a still life. The lemon could be satisfied and comfortable within its frame, enjoying and admiring itself as an image. Bathed by the swinging strokes of the brush and a foam of colors.

But the lemon gently shudders. It does not want to be a mere image, not just a representation but a presence unto itself. It wants to be utterly itself, a rounded-out “I”: a lemon.

But just as human consciousness must go through various stages of development in Hegel’s Phenomenology of the Spirit, in order to arrive at itself, so too must the lemon pass through different phases. But whereas human consciousness thereby becomes an independent subject through this process, by consuming objects, overcoming its counterparts by feeding on them, only the opposite path is open to the lemon. Mouthless, it must allow itself to be eaten, squeezed dry. The course of things takes a different path in its case.

***

So it flees the picture and the frame of representation, rolling in its fullness into the third dimension. It wants to find its way out of the forest of signs, out of the forest of brushes, and into life. It wishes to rebirth itself. And in no time it flows out of Courbet’s painting L’Origine du Monde and steps into the river. But it too never steps into the same river two times, but in accordance with Hegel, it experiences a transformation in the here and now, here in the studio and now in the flow of time. With this understanding of space and time it naturally does not only wish to rebirth itself but give life to a world of its own.

It wants to briefly approach Meret Oppenheim’s fur cup, warm itself with it, and rhapsodize about a surreal world in which objects develop lives of their own and are no longer subject to human reason as mere objects. But there it experiences something more terrible: it becomes pitiful; it become refuse. It does not roll out of the mouth of the womb in Courbet’s image but emerges from the gaping hole in the bottom of grilled chicken, out of the hole in its stomach and into the hell of trash.

Red is hostile. Bright yellow, the lemon can elevate itself to green through blue, transforming into a lime. The confrontation with red does not produce a lovely synthesis but a struggle for life and death, as between Hegel’s master and slave. For the red changes the yellow into orange in the mixing, and thus makes the lemon into its rival. But as if this were not enough, ultimately red covers every part of the lemon, denigrating it to a tomato, and the color pot of the despotic red becomes the tin can preserving a terminated life, and the blood of the fettered lemon flies everywhere, like in a splatter film.

***

But it is enticed by other colors, other forms. Driven to white-hot rage, the lemon blows itself to pieces, so that it can shape new forms from the scraps of itself. For example it become a pig, which as we know from Fischli/Weiss’ film The Least Resistance is never granted a long life. Maybe it would have preferred to remain a simple side dish to fish and meat.

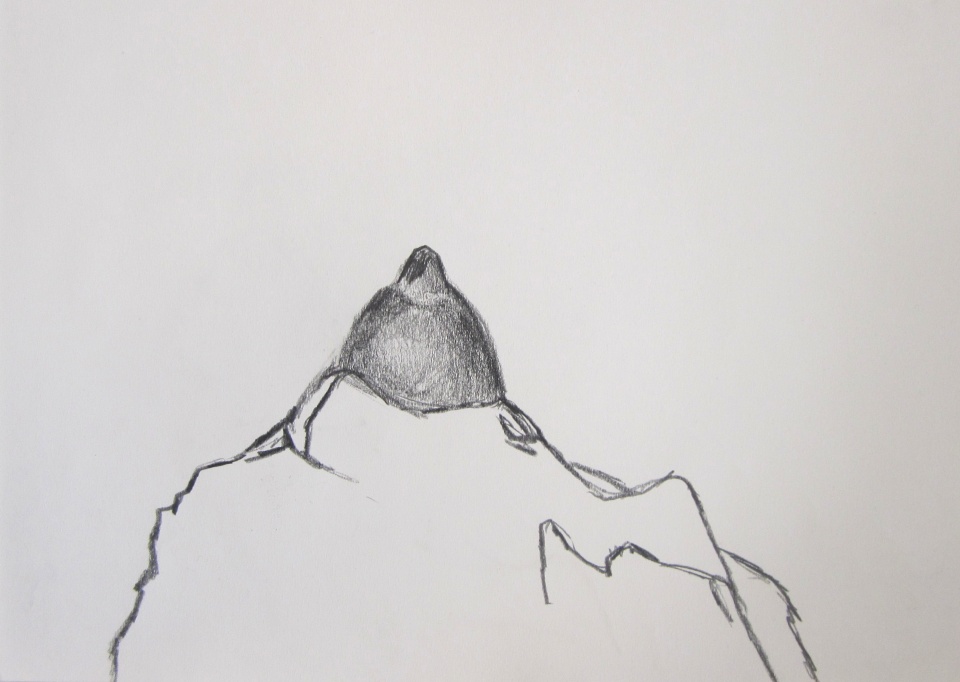

So the lemon roles back into its old role, and again it wishes to leave the image and transplant itself into its own “I,” but it betakes itself away from the land where the lemons blossom and transplants itself into the coldness of the office world and the ice of the mountains, foreign places. The lemon takes its revenge by crushing buildings with homes and heaths, rolling down into the valley, to the south, never arriving in its native land but constantly searching for itself in alien places.

How luck that I am a lemon, I think, that delicately shivers in the snowstorms of the world, in which every object has to be alike in order to satisfy the frigidity of abstraction. The lemon prefers to retract and avoid the reach of concepts and allegory. And the world retracts when it bites into a lemon, although it would much rather unfold itself—like in Hegel, in which thesis and antithesis, blossom and bud merge in synthesis into a higher being: the fruit.

To inseminate oneself? Although the erotic swing of Fragonard beckons on a blue-printed fabric, this world remains closed to the lemon. It cannot copulate with others but allows itself to be pollinated as a blossom. Its attempt to attain the genital phase is doomed to failure among its phallic relatives: the bananas.

***

The lemon finds itself a spot in the woods, and dreams of simply molding and disappearing. But death is also merely one of the many forms of change and transformation that it passes through on the search for itself.

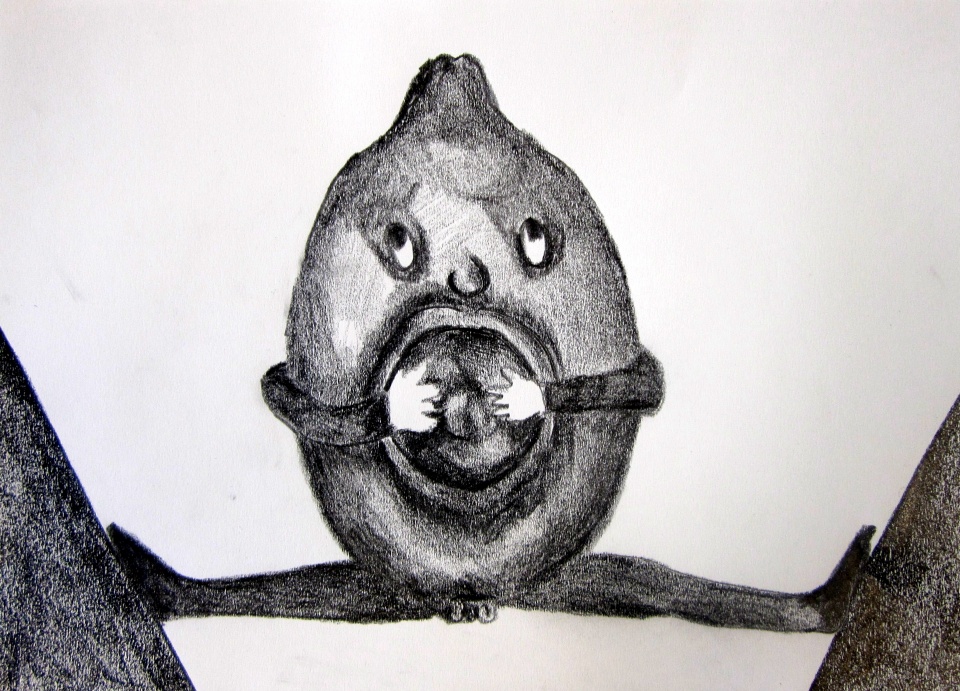

Although previously a moldy object of disgust, in the big cities it becomes an object of desire, multiplied on the market of consumption. The mirroring phase has been attained, once studied by the doctor Lacan who had hidden Courbet’s painting behind an erotic massacre by André Masson. Standing in front of the mirror, the “I” of the lemon is filled with a lust for power, capable of anything. It plants itself in the middle of Arcimboldo’s facial features of the human subject—but there you have it, the lemon is only a grotesque nose. The lemon’s “I” must submit itself to the “I”dentity of the human. To avoid the disappointment that follows, it multiplies itself in the mirror image of the world of products, whose “W” is emblazoned on tall buildings. Between them the lemon stands in line to finally arrive at its own meaning, but at the end a lemon press awaits, reducing the lemon’s “I” to a single quality in a gustatory game of sweet, sour, and bitter.

So the lemon remains a fettered object. But the chaosmos of its desires saves it from the still life and keeps it going, always driven by the desire to roll into a new role. The art of painting was never able to banish the lemon into the kind of still life that the French call nature morte. No, the death of representative painting was only the beginning of its journey. The lemon never fully arrived at itself. It is only native to the process of change.

Translation Laura Schleussner